One of the research questions is: can the system be used to measure dogs? But perhaps I should have been more specific: what size of dogs can effectively be measured with the pressure plate?

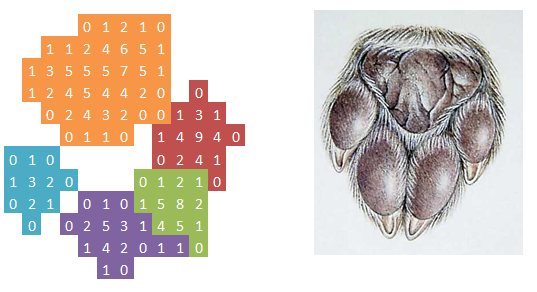

You see, the problem is that the pressure measuring plate has a sensor size of 7.02 mm (length) by 5.06 mm (width), which means that if the dogs paws get too small, it will only apply pressure to a couple of sensors. Why is this important?

When we try to divide a paw into subregions, based on anatomical structures such as the toes and the fat pad on the rear side, we need to be able to distinguish between the corresponding sensors. You can imagine that when the paw get’s smaller and smaller, there is a point where this is no longer possible!

Another issue is the sensitivity of the measuring device; in the example given here, the lowest measurable force is 0.4N (per sensor). Now if you try and measure a chihuahua that only weighs 2 kilo’s, you can imagine we start to run into some problems. Humans typically apply 120% of their body weight to the ground during normal walking, which roughly equates to 24 N in case of this chihuahua. Given that a dog has at least two paws in contact with the ground, you’re left with about 10-14N of maximal pressure per paw… Now if the paw is a couple of square centimeters in size, this amount get’s further reduced and you’re left with only a handful of sensors.

However, this problem works both directions of the spectrum; if the dog is too large his shoulder width might match the width of the pressure plate. The following example is a 20 kg dog of medium size, which is able to walk over the plate perfectly. But from our experience with humans, we know that this get’s increasingly more difficult when the shoe size increases (the toe’s tend to get cut off). Note: we don’t need to have all four paws on the plate during each trial, but when measuring in clinical settings, this is highly preferable due to time constraints.

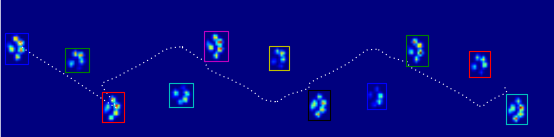

Based on the above, we want to see for which size of dogs the measuring plate can be used appropriately. To do so, we measured seven dogs in five different weight classes (1 to 5 kg, 5 to 15 kg, 15 to 30 kg, 30 to 50 kg and more than 50 kg) at two gait velocities (walk and trot). Each dog was being walked along the plate at a line, to make sure they walked in a continuous line and velocity. The clinicians also took into account on which side the dogs were being walked, since dogs are very accustomed to the way their owner walks with them and who walked with them (the owner or the clinician).

In total we now have measured the dogs three times per condition (at two walking speeds, with the owner and the clinician, at both sides of the dog), which equates to 24 trials per dog. One advantage of having multiple trials is that we can also see how reliably we can measure the dogs and have sufficient data to calculate averages when there aren’t statistical differences between the conditions.

On to the data processing!